This blog is taken from an interview I did for Triathlon Plus magazine back in May 2011.

Of all the hundreds of magazine features I’ve done, this is still my favourite. Normally I give training advice in this blog but seeing as it’s November I figured we could all do with some inspiration for the winter months ahead.

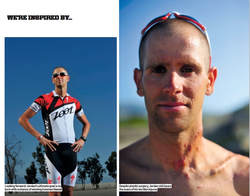

Left for dead by a hit and run driver while out training, pro triathlete Jordan Rapp’s life was saved by a passing stranger…

It’s a bright spring evening in California and pro triathlete Jordan Rapp is hammering along a quiet Ventura County lane on his Specialized TT bike. He has high hopes for the upcoming season after winning Ironman Canada and Ironman Arizona the season before. At this moment in time, he only has one thought on his mind: “I hope I finish this interval before I reach the traffic lights.”

And that was the last thing he remembers before he was the victim of a terrible hit and run incident. Left in a lake of his own blood, he had minutes to live. Ask him what happened and he won’t know.

“I was finishing up some intervals, preparing for the Oceanside Ironman 70.3 triathlon the following Saturday. The next thing I recall was two days later, choking when the doctors pulled a breathing tube out of my throat. I don’t really have the words to describe what happened to me on that day, because I have no idea.”

Fortunately for Rapp, Chief Petty Officer Tom Sanchez was driving back from his Naval base, 48-hours before he was due to fly to Afghanistan. “I was just on my way home, thinking about my family and what I might be having for supper. I was in no way ready for what happened next.

“At first all I saw was a line of cars. As I drove by two navy guys slowed me down and asked me if I knew first-aid. I could see from their badges that they’d had the same training as me, but I said yes anyway.

“I saw a cyclist lying on his side, in a pool of what I assumed was transmission fluid. It turned out to be his blood. He’d been rolling around in it and it totally covered his mouth, his eyes and even his shoulders. I rolled down the collar of his cycling jersey and saw this massive hole in his neck, at least seven centimetres wide. It was pretty sick.

“I tried talking to him because his eyes were partially open, but he just moaned. When I tried to lay him down, he would struggle back up like he was doing a push-up. He needed to calm down because I couldn’t help him if he was fighting me. I rolled him onto his back and went to get my combat vest, which contained a medical pack. I took some gauze and tried stuffing the hole but it was ridiculous, like dropping napkins into an ocean. So I pinned him down, put my hand inside his neck and felt around until I felt something pulsating inside. He wasn’t even reacting to it so I tried pinching to stop the blood flow. I couldn’t even feel if I was doing anything. I just held it tight until an ambulance came.

“When the paramedic arrived he swapped his hand for mine, and Jordan was rushed off to hospital. I was left standing there wondering what the hell had just happened. It was surreal. One minute I’m driving home, the next I’ve got my hand in this guy’s neck. To have that whole thing happen to you is pretty intense. Yes, I’m in the military but I’m a carpenter by trade. We do have combat training but I’m not normally the guy shooting guns or breaking down doors.”

While Rapp was being rushed to hospital his wife Jill was at home panicking: “I called Jordan’s phone several times, and it just rang through and nobody answered. Then I started calling hospitals but he wasn’t at any of them. I knew there was something wrong. I was freaking out so I called 911 and gave a description of him as missing. I couldn’t even tell them where he might be. It was getting dark too. He could have gone off the edge of a cliff for all I knew. Within 10 minutes they called me back and matched his description to an accident that had happened.

“Minutes later the Sheriff called me, and the first thing he said was: ‘We’ve found your husband and he’s been the victim of a hit and run.’ So I immediately thought he was dead. I dropped the phone on the floor, but my housemate picked it up and heard the Sheriff saying ‘No, no, no he’s alive and he’s on his way to the hospital.’ He couldn’t give us the full extent but he said it was really serious. It was like one of those nightmares that you never expect to happen to you.

“We didn’t really hear anything from the hospital staff when we got there. We just sat there for four hours, totally freaking out, not knowing if he was dead or alive. I confronted them, but they couldn’t tell me what was happening. It turns out they were scanning him for brain damage, while a plastic surgeon was doing emergency work on his severed neck.

“I eventually saw him at one o’clock in the morning and his face was all puffed out. I didn’t know if he’d do triathlons again, but I knew he was going to live.”

Rapp is still unsure of how it happened and can only speculate: “I was riding on this really quiet road. If someone had told me I’d have an accident somewhere, it would be the last place I’d ever guess. It has a really wide shoulder. You could ride two abreast in this shoulder and cars could pass by easily on the road without having to pull out. There’s great visibility, no trees, a long line of sight. It’s a safe road.

“We think I went through the side window of the car, so all the glass caused the marks you can see (he has massive scarring on his neck). You have three main jugular veins supplying your brain with blood and it sliced through two of them. They said I lost almost four litres of blood. When Tom Sanchez arrived I was two and a half minutes away from death. It took another eight minutes for the ambulance to arrive so there’s no question that Tom saved my life. It’s a fact that without Tom I would be dead. No Tom, no Jordan.

“I also broke my shoulder blade and my collar bone, which they plated. I broke my cheekbone too, so now I have titanium plates all across my face. I’m fortunate in a way because my glasses hit my eye and cut me open, so they used that cut as an insertion point for surgery on my cheek. At least the scarring is mostly on the inside of my mouth.

“I had bad nerve damage too, so I couldn’t use one of my arms. You can still see it’s much thinner than the other. I call it my ‘Andy Schleck bicep’ (after the skinny Tour de France cyclist) although it’s grown a lot bigger these days.”

“During my 18 days in hospital Tom came and visited me, but my memory of that time is very patchy. It wasn’t like I recognised him. I was heavily sedated and I only remember it because I saw pictures afterwards. It seemed strange that I had no memory of this guy who saved my life. Shortly afterwards he got shipped out to Afghanistan for eight months, but we kept in touch by email and Facebook.

“At this point, I didn’t even think about triathon. I certainly felt like I didn’t want to ride a bike anymore. So, for the whole time I was in hospital, and for at least the first bit when I came out I never imagined I’d compete in triathlons ever again. I felt that triathlon had put me in this place.

“Over time I changed my view. I love doing triathlon and I didn’t want to give it up because I was afraid. You can get hurt crossing the road and almost anything has a risk attached. I heard of a guy at a pool-party who dived in and broke his neck and is now paralysed. But that doesn’t mean none of us should swim.

“I wasn’t allowed to train outside for three months so my first ride after my accident was on an indoor trainer. I was on blood thinners because my neck had torn so badly inside that they were worried I could have a stroke. So if I’d crashed I wouldn’t have stopped bleeding. Even training inside was tough. I couldn’t support my own weight because I’d broken my collarbone, so I was sitting upright and balancing on one arm the whole time.

“I remember going to watch the Wildflower Ironman 70.3 for my sponsors Specialized, which was the first time I’d left the house for a long time. It felt so good to be somewhere other than sitting on the couch. That’s when I first thought about doing Ironman Arizona again, and I remember telling people. Nobody really believed me and I don’t even know if I believed it myself. But I needed something on the horizon to keep me going. Ironman Arizona would only be eight months after my accident, so I knew it would be tough.”

“It took me a long time to pluck up the courage to ride outside again. Every day I was like: ‘Right, I’m going to go and ride today’, but I didn’t have the nerve to do it. Finally, I asked some friends for advice. Dan Empfield from Slowtwitch.com cut to the chase by saying: ‘If you want to do it, go do it. If you don’t, then don’t. It’s not like you’re any more likely to get hit than before.’ So eventually I did and the hardest part was just making it to the end of the block.

Returning to cycling was one thing, but it was running that caused Rapp the most problems: “Everything got hit so hard and knocked out of whack from my accident that when I tried to run I got really bad ITB pain. It was so bad that I had to stop after a minute. I couldn’t even see a chiropractor because I had to wait three and a half months for everything to heal first.

“So I used the gym to start from scratch again. Slowly I built up my running, but the first time I ran for an hour was only eight weeks before Ironman Arizona. Other than that I guess I was running 15-minutes three times per week.

“My goal was still to win the race though. I asked myself how much the other guys wanted it. Some of them were only there for Hawaii qualification points and I knew I wanted it more.”

While Rapp was building his fitness, Tom Sanchez was still serving in Afghanistan, albeit with a few special perks thanks to his newfound hero-status. Rapp can’t help smiling as he recounts the story: “Tom said that if he added up all the parcels he got in his entire Naval career it would be less than he got on that one trip. He was getting presents from people even I didn’t know. People I’d never met were emailing me and asking for Tom Sanchez’s postal address in Afghanistan. The triathlon community came together and put together a whole care package. One guy who worked for a bedding firm sent him a set of expensive sheets and pillows. Tom said he had nicer bedding in his barracks than he did at home! There was another guy who worked for a company that made casino supplies and he said he’d send Tom some playing cards. I guessed he’d send a few decks, but he sent 2000! It became like a running joke. He couldn’t even give them all away.”

The US Navy even flew Sanchez back home two days early, so he could travel to Arizona to watch Rapp make his eagerly awaited Ironman comeback: Sanchez recalls: “The gravity of everything that happened hadn’t really hit me until that point. I was sitting on the side of Tempe Town Lake, listening to the announcer before the race start. It was cold and misty, we’d got up early and I was tired. And I wasn’t even the one competing. To think about the level that Jordan was about to race at was so physically amazing. Eight months earlier I thought this guy was dead. And now here he was racing an Ironman. Sitting beside his wife Jill I began to choke up, and she said: ‘don’t you start, you’ll get me going too’”.

Amazingly, just eight months after his life-threatening accident Rapp finished in fourth place, recording a time of 8 hours 16 minutes. In almost any other year his time would have guaranteed him first place.

“I was first off the bike, but Timo Bracht was hot on my heels and he broke away in transition. He’s not the sort of guy who’s going to fall apart. I was in second place for most of the run, but at the 25km mark, I went from four minutes per kilometre right down to four minutes thirty. It was like a light switch that came on almost immediately. I knew I’d given all I’d got.

“When I reflect on that result am I happy with it? I wanted to win, but I was still proud of finishing well. Whether that was fourth or sixth didn’t matter so much.”

His wife Jill adds: “If you see pictures of Jordan at the finish you’ll see he’s very emotional.”

Rapp agrees: “Tom was at the finish line and gave me a really big hug, along with mine and Jill’s families. We’ve become great friends since the accident. There was also a guy who came up to me who’d set a course record in his age-group the year before. A car had hit him in September and he was still in a rough condition. He was getting choked up telling me his story and I was getting choked up listening to him. He said seeing me made him believe he could make a comeback too.